Beyond the Catch: How Trout Fishing is Good for Wellbeing

- 20/09/2024

By Bruce Quirey

Even when not at work, Cohen Stewart can often be found on a river. The Southland Fish & Game officer likes to spin-fish for trout using soft baits in the lower reaches of his local waters. During the fishing season, he usually wets a line for a couple of hours at least once a week.

“One of my favourite spots is the lower Makarewa River, which is just 10 minutes’ drive from my house. I have a fondness for this spot as it is where I learnt to trout fish as a teenager,” Stewart says.

“As we now know from Fish & Game-supported research, the connection I have with this river may well boost my wellbeing.”

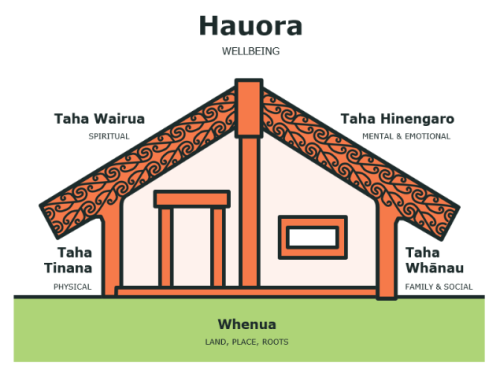

Almost 40 years ago, Sir Mason Durie, an advocate for the integration of Māori perspectives and values in health services, developed a holistic framework for health. The distinguished psychiatrist and academic called the model Te Whare Tapa Whā.

The model presents a holistic (hauora) conception of wellbeing, symbolised as a wharenui (house) with four walls representing interconnected components: taha hinengaro (mental), taha whānau (social), taha wairua (spiritual), and taha tinana (physical), supported by the whenua (lands and roots).

Today, Sir Mason’s framework is widely used in New Zealand as a model of holistic wellbeing for both Māori and non-Māori.

You might ask, what does this have to do with trout fishing? Here’s the hook.

Research initiated by Fish & Game suggests a connection between trout fishing in Aotearoa New Zealand and the four elements of wellbeing - mental, social, spiritual and physical.

Stewart came up with the idea of the wellbeing research project, beginning with a 10-week qualitative pilot study.

“The idea for the wellbeing study came about when I was doing some reading and stumbled across the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, which translates to ‘forest bathing’ or ‘taking in the forest atmosphere’,” he says.

“With this technique, participants go and simply connect with nature in forested environments. Scientists have been able to show that cortisol (stress hormone) levels drop when exposed to forested environments.”

Further research has shown exposure to green space (gardens, parks) and blue space (lakes, rivers, oceans) can positively affect mood and self-esteem and reduce perceived stress.

Stewart could see that trout fishing exposed people to green and blue space simultaneously and offered a multisensory experience.

“I thought, surely trout fishing is positively affecting the wellbeing of anglers across the country.”

The Pilot Study

Medical student and researcher Iritana Bennett-Fakahau says the immersive" experience of trout fishing has re-inspired her in the cultural practices of mahinga kai.

Iritana Bennett-Fakahau, a then-third-year medical student at the University of Otago, took on the pilot project and spent the 2022-23 summer working on a qualitative study.

Bennett-Fakahau interviewed nine trout anglers – seven men and two women - in Otago and Southland, beginning by asking what wellbeing looked like to them. Their answers identified mental, social, physical, and spiritual aspects.

When asked to describe a recent trout fishing trip that was particularly fulfilling, they talked about a variety of trips, types of water, and ways of fishing. And when asked how trout fishing lined up with their own definition of wellbeing, they believed trout fishing could improve various aspects of their wellbeing.

Analysing the responses, Stewart and Bennett-Fakahau concluded trout fishing could contribute to all elements of wellbeing within the Te Whare Tapa Whā model - mental, physical, spiritual, and social.

Trout fishing promoted feelings of happiness, helping people to connect with self, others, nature and place, and to disconnect from stressors. It also provided exercise and an opportunity to think simply and focus.

“It was clear from the interviews that trout fishing created positive emotions, could support spiritual wellbeing by connecting people with nature, provided a form of physical exercise, and connected people with others,” Stewart says.

“As such, trout fishing may hold great potential as an activity that improves the wellbeing of participants, and we look forward to conducting further work in this area.”

Connecting with friends and nature among blue and green spaces, a trout river is a wonderful place.

‘Immersive Experience'

Before taking up medical studies, Bennett-Fakahau completed a Degree in Health Science majoring in Māori health, and has been a community support worker for people with disabilities. She grew up in a family of Maori-Tongan and New Zealand European decent on the Kāpiti Coast.

“My Māori culture is quite important to me,” Bennett-Fakahau says.

Following her interests in community health, it seemed a natural progression for her to take up the research project. She did not have much fishing experience, although as a teenager she had helped her aunt catch and measure eels near home as part of an environmental study.

“I'd get pipi at the beach, and I had held a rod as a child, but I had never caught a fish.”

To gain some perspective, Bennett-Fakahau spent a day trout fishing with Stewart, and described the experience as “immersive”.

“You don't really fish with people if you're along the river. You're normally by yourself in your own little bubble,” she says. “Just being out in the environment was immersive compared to working on a laptop.”

She says her fishing outing has motivated her to get out and collect pipi, mussels and tuna, practising traditional mahinga kai.

From the angler interviews, Bennett-Fakahau observes that the reasons why males go trout fishing may be complex and nuanced.

“The male perspective was eye-opening in the sense there was a lot of feeling and emotion towards fishing,” Bennett-Fakahau says. “I didn't realise it provided so much joy and peace and comfort. I always had the assumption that people liked to fish and that was it - a hobby. But there was so much more to it. It seemed like it was, or could be, the central part to their mental health and wellbeing.”

Common themes of spirituality, the importance of kindness, the environment and a higher sense of self came through. The interviews also highlighted themes of having time alone to think and reflect. Fishing companions would also talk about things that might otherwise be left unspoken.

Need for Intervention Programmes

Dr Shyamala Nada-Raja says the role of nature-based interventions for mental wellbeing is a new and growing area of research showing some promising results.

Dr Shyamala Nada-Raja, senior research fellow in Vaá o Tautai – Centre for Pacific Health (University of Otago) – supervised Bennett-Fakahau during her 10-week summer studentship with Fish & Game. Nada-Raja has an academic background in mental health and suicide prevention research. She notes that mental health has been a challenging field for both clinicians and researchers alike for several decades in Aotearoa New Zealand.

“Mental health services are underfunded and it has been difficult to recruit specialist staff in this area. With rising rates of poor mental health, especially among our young people, the sector is in crisis mode on a regular basis,” Nada-Raja says.

Despite these challenges, several innovative and community programmes have been implemented, but capacity to deliver is always compromised by the rising demand for such services and lack of sufficient resources, she says.

“This challenge highlights the need for innovative and more easily accessible intervention programmes we can implement using existing resources.”

The role of nature-based interventions for mental wellbeing is a new and growing area of research showing some promising results, she says.

“The research we are focused on addresses a neglected and hard-to-reach population with mental health and wellbeing issues, namely males of all ages in our communities.”

Online Survey

The next stage of Fish & Game’s wellbeing research is currently underway, and more than 1800 New Zealand anglers recently took part in an online wellbeing survey.

“We decided to further investigate and quantify the relationship between trout fishing and wellbeing through a larger-scale study involving licence holders from across the country,” Stewart says.

“The information gained from this research will enable us to more definitively determine the link between trout fishing and wellbeing and identify the critical elements of trout fishing that have the greatest impact on wellbeing.

“For example, do all types of trout fishing provide the same wellbeing benefits?

“Does catching trout enhance mental health?

“Does direct contact with the water (wet wading) offer additional wellbeing benefits?”

The large-scale survey will put Fish & Game in a strong position to provide information that anglers can use to optimise their wellbeing while trout fishing, Stewart says. It could also help inform the development of a trout fishing-based wellbeing intervention.

Trout fishing and wellbeing: what anglers say

Mental

“You do need a place, somewhere to reset, somewhere just to take a pause, take a breather, and that’s what it gives me.”

Physical

“It gets you out on your feet and into fresh clean air.”

Spiritual

“I’m nourished mentally and spiritually by being out in the natural environment.”

Social

“I take a lot of people fishing, and in that way it’s a wonderful connection. That’s memories that they keep forever.”.