Hugh Creasy column for Reel Life March 2018

- 27/03/2018

Creasy's Column - By Hugh Creasy

A maize crop has been harvested and the Canada geese are moving in. There are hundreds of them, and a few black swans and plovers – a noisy congregation with the swans as silent celebrants.

On the mountain screes high up where the vegetable sheep grow and dwarf hebes throw seeds to the wind after a hard summer, there is the crackle of ice in the mornings. The shingle breathes as the sun strikes, a slow susurration as particles expand. Stones are clumping – ice bound, soon to be gripped in winter’s chill.

Mountain daisies look dead, dessicated, flowers long gone, their root systems hard, fibrous, searching for protection in rocky fissures. Winter is coming. At altitude it is meaningful and the plants have adapted.

Lower down the evening freeze is thawed by midday, and the chill waters descend to the lowlands where fish and birds search hungrily for sustenance. Cool water wakens the trout and the insects they feed on. Where mayflies and caddis have survived the heated flows of summer, they now rise in the mornings and evenings, hurrying to mate and spread their eggs. Nature’s in a hurry. Another month or two and it will be too late.

To survive the winter, birds need to feed. If they don’t have a protective layer of fat, the cold will kill them. Trout will be spawning, and they need strength to fight for the right to cover the redds where the hens are already feeling the urge to mark a territory.

To survive the winter, birds need to feed. If they don’t have a protective layer of fat, the cold will kill them. Trout will be spawning, and they need strength to fight for the right to cover the redds where the hens are already feeling the urge to mark a territory.

Geese in the paddock next to the river are skinny. They are still recovering from the rigours of the moult and a hard summer raising their young. Hunters often shoot them too early in the season and complain that they are scrawny and poor eating, and their carcasses are left to rot. Given a month or two for the fat to cover their breasts and the eating quality rises enormously. A Canada goose in prime condition makes a marvellous roast, but the bird must be carefully chosen and prepared.

It’s the same with trout. They are at their peak as a game fish just before spawning in late autumn. Their flesh will be succulent and oily. But take only a brightly silvered fish, deep in the stomach with no darkness of skin. Return the dull ones. They will grow brighter as the season progresses. There are exceptions to the rule, of course.

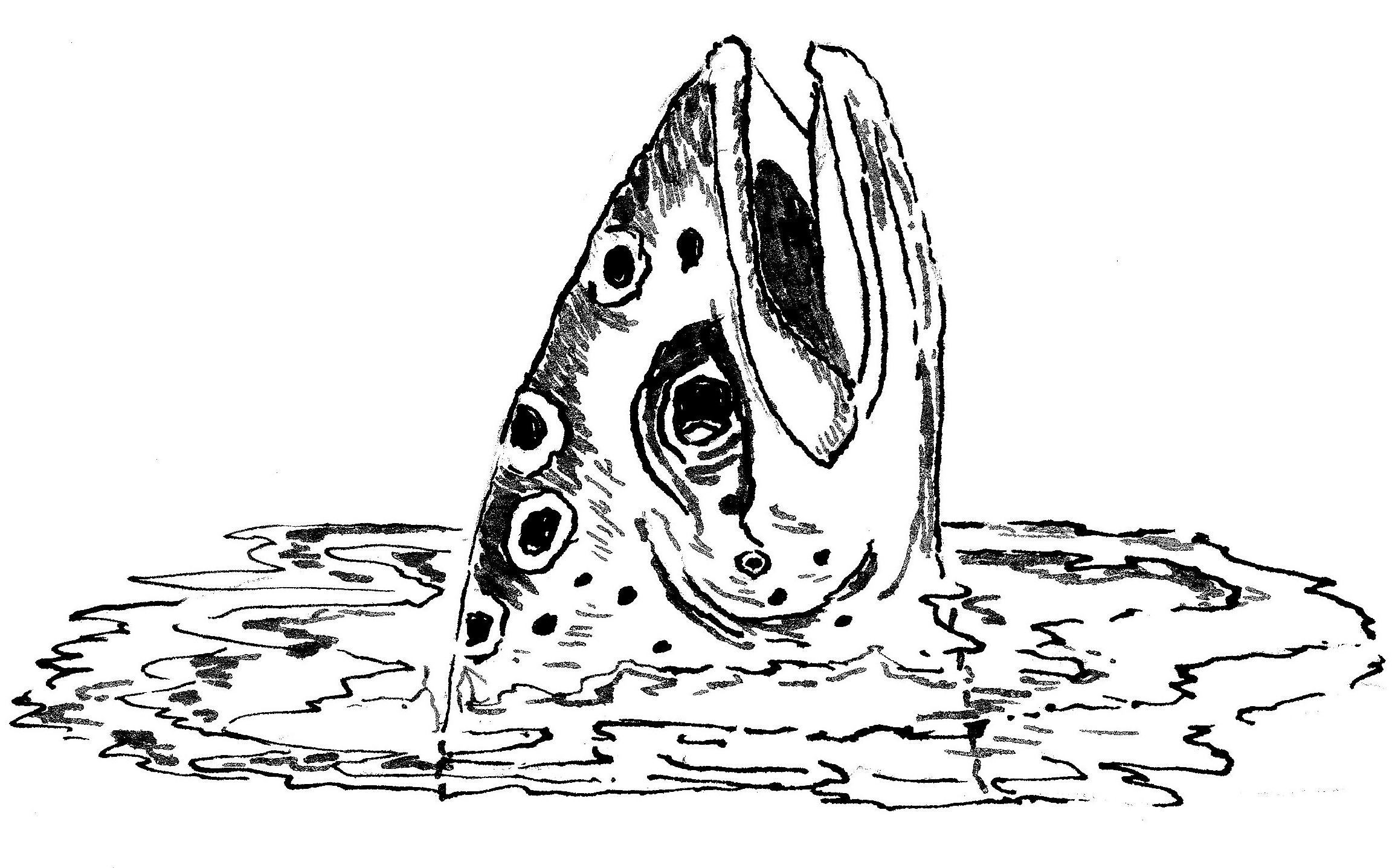

A few years ago I was fishing one of the southern West Coast lakes. Its inlet flowed through heavy beech forest, and a tangle of fallen beech had to be negotiated to reach open water. The fish I spotted were cruising over golden sand heavily streaked with leaf mould. They were big brown trout and because I stood in shade with the sun behind me, I was invisible to them. I flicked a big damsel nymph to the nearest one and it took it with great gusto. It was more by good luck than good management that I landed it, after a battle through sunken branches and heavy weed.

The fish weighed three kilos was deep in the body, and apart from a pale strip of belly was coal black. I killed it and opened its gut. It was full of hard-cased caddis. It’s flesh was bright orange and there was a thick band of fat on its skin. It was a creature of stunning beauty and had a flavour to match. I think its colour came from a combination of tannin-stained water, caddis and snails. In the lake itself the fish were of normal colouration.

Although tannin-stained, the water had a clarity that was quite deceiving and stepping off the bank had to be carefully judged. The forest acted as a filter and stabilised the flow in an area where rainfall is measured in metres. It is only when you are in wild, virgin country that you get an inkling of what the rivers must have been like before settlement and development turned them into drains, largely unfit for drinking and marginally of use for recreation.

Planting the margins will work wonders on our rivers, especially those that run through urban environments. Perhaps, in a few years, urban dwellers will once again wonder at the richness of our natural heritage as they swim the pools of rivers and streams, unworried by swallowing the occasional mouthful.

In the meantime we fish the slime and politics-infested, near-poisonous rivers where trout survive by the barest of margins. Still, the memories are good, and the purity of southern waters gives us an idea of great possibilities. Back to Reel Life.

Back to Reel Life.