Hugh Creasy's column for October Reel Life

- 24/10/2019

- Richie Cosgrove

It was early in the season when I came across a bog at the head of a stream, where gorse thickets climbed the hillsides and raupo and blackberry edged the swampy valleys.

Dragonflies hovered over deeper pools and clouds of smuts clouded the air under clumps of manuka, flowering and alive with buzzing honeybees.

The muddy edges were strewn with feathers and the prints of webbed feet showed clearly.

Mallard ducks have to go somewhere to moult and they gathered in the gorse with drinking water handy.

The process must be debilitating and the birds were vulnerable to predators.

My presence was an invasion of their privacy, and I returned to the stream’s headwaters a few metres away.

There the water ran clear from springs and damsels darted over a pool where bullies patrolled their tiny territories, and dined on invisible insects and challenged each other with spread fins and elaborate display.

There were no trout to be seen, but on a slippery strand of stone where the stream ran thin, there were a couple of torrent fish, tiny battlers whose streamlined bodies split the fast water.

Just to see these creatures without the aid of an electric fishing machine was surprising and I congratulated myself on my powers of observation. What I needed was similar powers to see the trout in heavier waters downstream.

The stream tumbled over large rock formations, finding cracks and crevices that concentrated the water’s power and oxygenated the water.

Just a few metres from the headwaters there were freshwater crayfish, claws outstretched to catch any fleshy morsels that might pass by.

They would make easy pickings for later in the day, when the billy was boiling and some sweet-fleshed crayfish, a dash of salt and pepper and buttered bread would make a sweet sandwich to complete a wild foods dinner.

A hundred metres further downstream a small seepage entered the main flow from the foothills.

It crossed a boggy meadow dotted with sedges.

If ever there was great habitat for maturing whitebait this was it.

Another hundred meters away there was a patch of raupo in deep water, green with duck weed.

The swamp formed a barrier against cattle making their way to an inviting pasture, and the main stream flowed through a steep-sided valley – sheer rock walls that would prevent access.

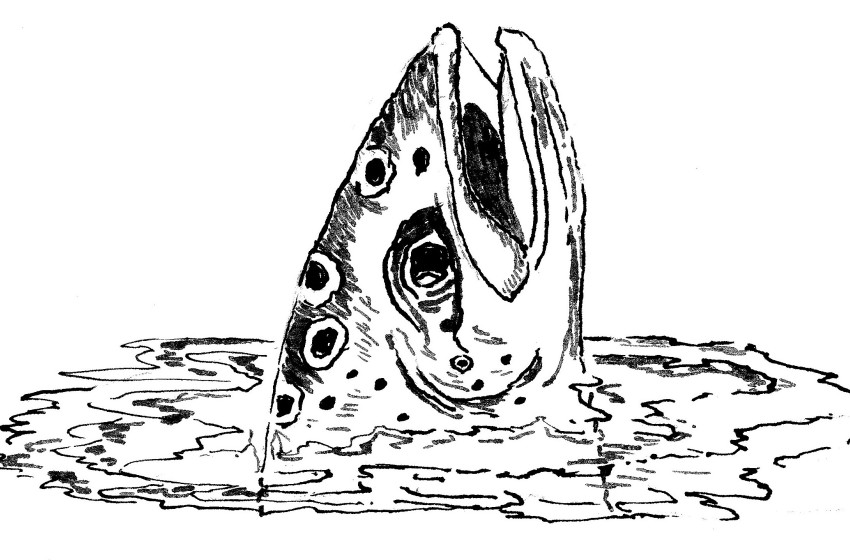

Further downstream and in bigger water there were schools of whitebait keeping to shallow water, sidling their way upstream.

Here there were trout-- fat, belly-bulging trout stuffed to the gills with tiny slivers of silver.

They were inert at the head of the pool and in line astern to its tail, a dozen of them, none of them monsters, but sated and not feeding.

The whitebait sidled past and into the rapid at the head of the pool – only a few hundred metres to go to the safety of the bog and the swamp.

I wished them luck, and prepared to tempt a take or two from the main predators.

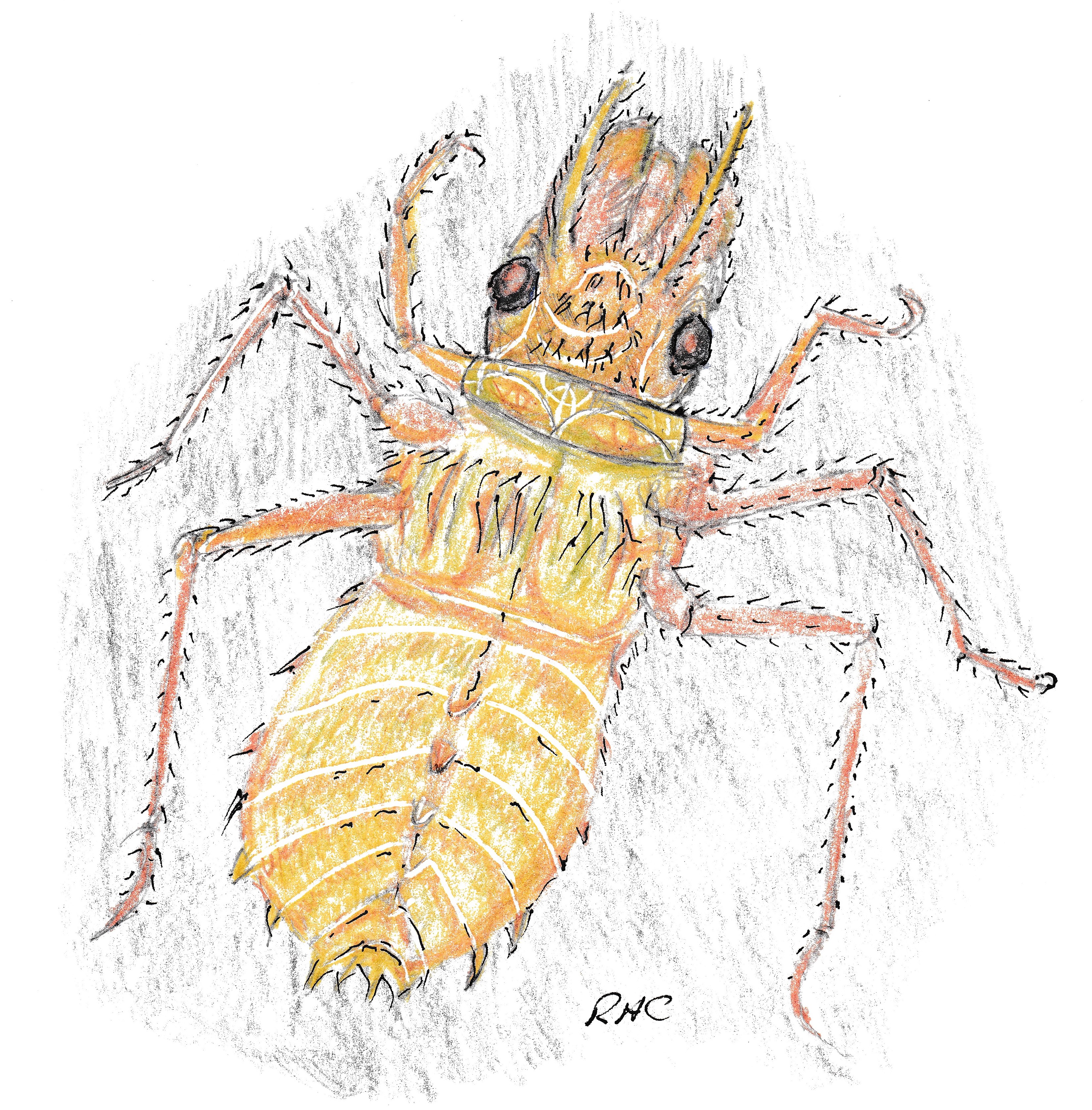

dragonfly larvae

A whitebait imitation would have been the logical choice, but I decided it was a bit too obvious.

The trout had had a gutsfull of these and I wanted to shake their sensibilities and induce a strike.

So I tied on a big fat dragonfly larva imitation tied on a #8 hook.

My theory was that a fly of such big proportions with a bulging head would shift water as it was retrieved and the movement might be enough to awaken such somnolent beasts.

Most anglers would leave such unlikely targets and go for bigger, more lively fish downstream.

But I have always been content to go for a lesser prize, mainly because I loved the setting, the survival of the whitebait, and the challenge of catching a fish against the odds.

And I did, a long leader did the trick, and the plop of the nymph entering the water caused a surge of interest from the trout and one turned and snapped at the nymph, missed it and pursued it downstream where it was taken by another, smaller, fish.

I struck and the fish swirled around its restricting pool, frightening all its neighbours, till I brought it to the net.

A nice little half kilo brown that would do nicely for supper.

Then it was back upstream to where the koura were spotted. In my pack I carried a muslin net for taking samples.

It’s only a small item but big enough to capture crawlies, as we had called them when children.

I need to shift some boulders on the bottom but there they were, a family group of half a dozen, with the largest all of 7 centimetres in the body.

I picked three of the largest and left the rest.

That evening, as the sun set over the western hills, a dab of butter, some salt and pepper and I had an entree and main course prepared in minutes.

It’s a hard life, being a survivalist, living off the land, battling the savagery of nature. In the morning I’m going home to pick up a whitebait net.

I’ll once again challenge the might of nature, sitting down and watching for tiny fish swimming over a sheet of white plastic.

I’ll once again challenge the might of nature, sitting down and watching for tiny fish swimming over a sheet of white plastic.

The fritters are a sweet reward for meeting the challenge of the wild.

Some people climb mountains, some swim the depths of the ocean, and some venture to wild jungles where violent animals can take a life with the sweep of a paw.

I prefer the wilds of New Zealand where the wilderness can be kindly, if you know what to look for.