Creasy's Column for Reel Life October 2018

- 29/10/2018

By Hugh Creasy

Geese are creatures of little brain. But what they do have gives them a courageous and cunning streak that leads to survival against the odds. Being confronted by a domestic goose defending its brood can be a disconcerting experience, and their attacks on trespassers often end with a feathered victory. I’ve come across Canada geese, nesting in deep forest but always within reach of water, or in gorse-covered headwaters where bogs give protection against predators. Their selection of nesting sites denotes a practical application of what little intelligence they possess. If a goose has a brain smaller than a pea, its survival must mean the brain is made full use of – much to the chagrin of humans whose brains are hundreds of times larger, yet we build leaky homes on flood plains and on earthquake faults.

It was a confrontation with a pair of Canada geese and its brood that drew my admiration. I was casting to a likely lie, when the family bobbed downstream towards me, the youngsters pretty in their mottled golden down. I kept still as they approached and they were only a few metres away when the gander spotted me. He let out a call that sounded like a dog barking, then stretched out his neck, spread his wings and hissed. The rest of the family scattered across the river, paddling like crazy, led by the goose whose plaintive honking had them all gathering astern as she reached the far side.

The gander spun around and took off, flying low, skimming the water before disappearing on the far bank, no doubt rejoining his family. His first reaction at the sudden confrontation was to attack, though he retreated at the first opportunity. It was a reaction that spoke of survival skills that have led to Canada geese being treated as a major threat to the economic well-being of high country landowners who have declared war on the birds -- a war that at present they show no sign of winning.

I like Canada geese. I like eating them, hunting them and being their principal predator.

It’s much the same attitude as I have towards trout. Trout are creatures of great beauty, designed by nature to fit their environment.

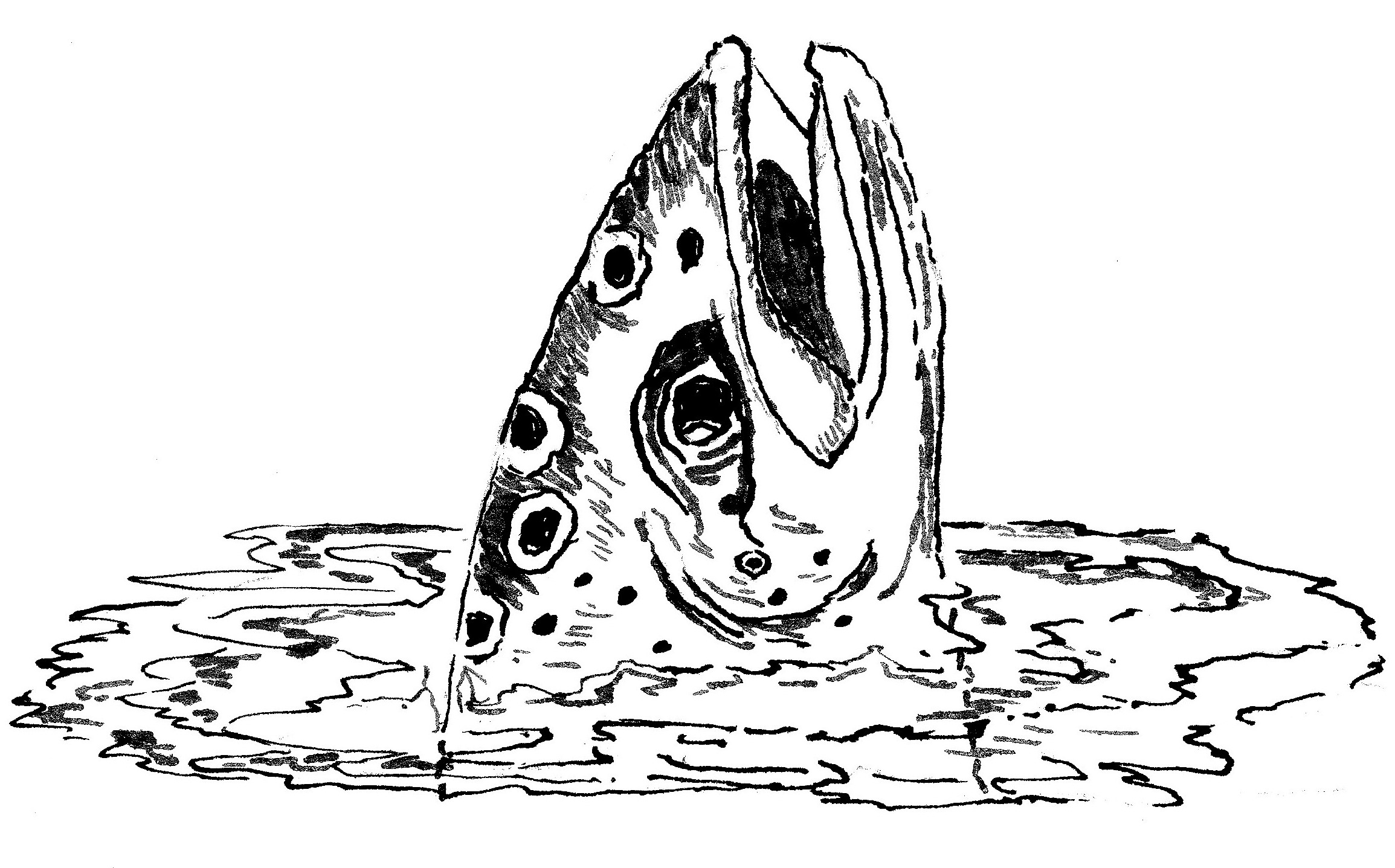

Ring of the rise.

They have no equal when it comes to survival skills, as long as their environment remains as nature intended. But the rapacious nature of humans has altered most of the planet’s environments to the detriment of themselves and every other branch of the natural world.

Adaptation has become the key to survival, and geese and humans are very good at it. So are rats and mice and bacteria. If you were going to bet on the winners in the race for survival, bacteria would lead by a mile. But even they could not survive a dead planet. Life as we know it requires clean air, light, heat and clean water, all pretty basic stuff which humanity seems bent on destroying.

These rather depressing thoughts were engendered during a lull in the pursuit of trout, when all went quiet, no rising fish, no birdsong, no wind and even the song of the river itself seemed hushed.

Then, from upstream came the chug, chug, chug sound of a bulldozer, its steel tracks shrieking as it ground its way to the water’s edge. Its blade came down, dug into gravels in the shallows and slowly made its way downstream, before turning towards the bank with more shrieking of tortured metal, and turned once again towards the water. It was crossblading. This is a term used to describe the reshaping of a riverbed and surrounds to lessen the effects of flooding. Its effect is to kill all forms of life on the river margins for very little benefit. It can also have the effect of turning floodwaters into a race, increasing the speed of the flow so that areas downstream from the areas crossbladed suffer far more damage than if the river was left alone. What may be a benefit to some, certainly isn’t a benefit to others. The immediate effect is to loosen silt from the crossbladed areas and allow it to flow and settle downstream, blocking the interstices between cobbles and boulders on the riverbed and ruining habitat for the fauna of the river.

Crossblading is done when river levels are low and machinery has access to sensitive areas of the river. It is a form of vandalism carried out, usually by local governments, as a sop to nearby landowners, instead of real river protection work that costs money.

And, of course, it makes anglers bad tempered and upsets geese and ducks trying to bring up their youngsters in trying circumstances. But these river beds are also nesting sites for wrybills and stilts, and are prime feeding areas for many other birds.

A day’s fishing spoilt it may be for an angler, but it is life and death to nesting birds, and it means a slow death to the fish of the river deprived of a prime food source. What is most annoying is that it is so unnecessary, when with a little forethought and planning, it can be avoided.

Oh, well, there’s always another river to fish – until there are no more rivers to fish.