Hugh Creasy column for January 2021

- 21/01/2021

- Richie Cosgrove

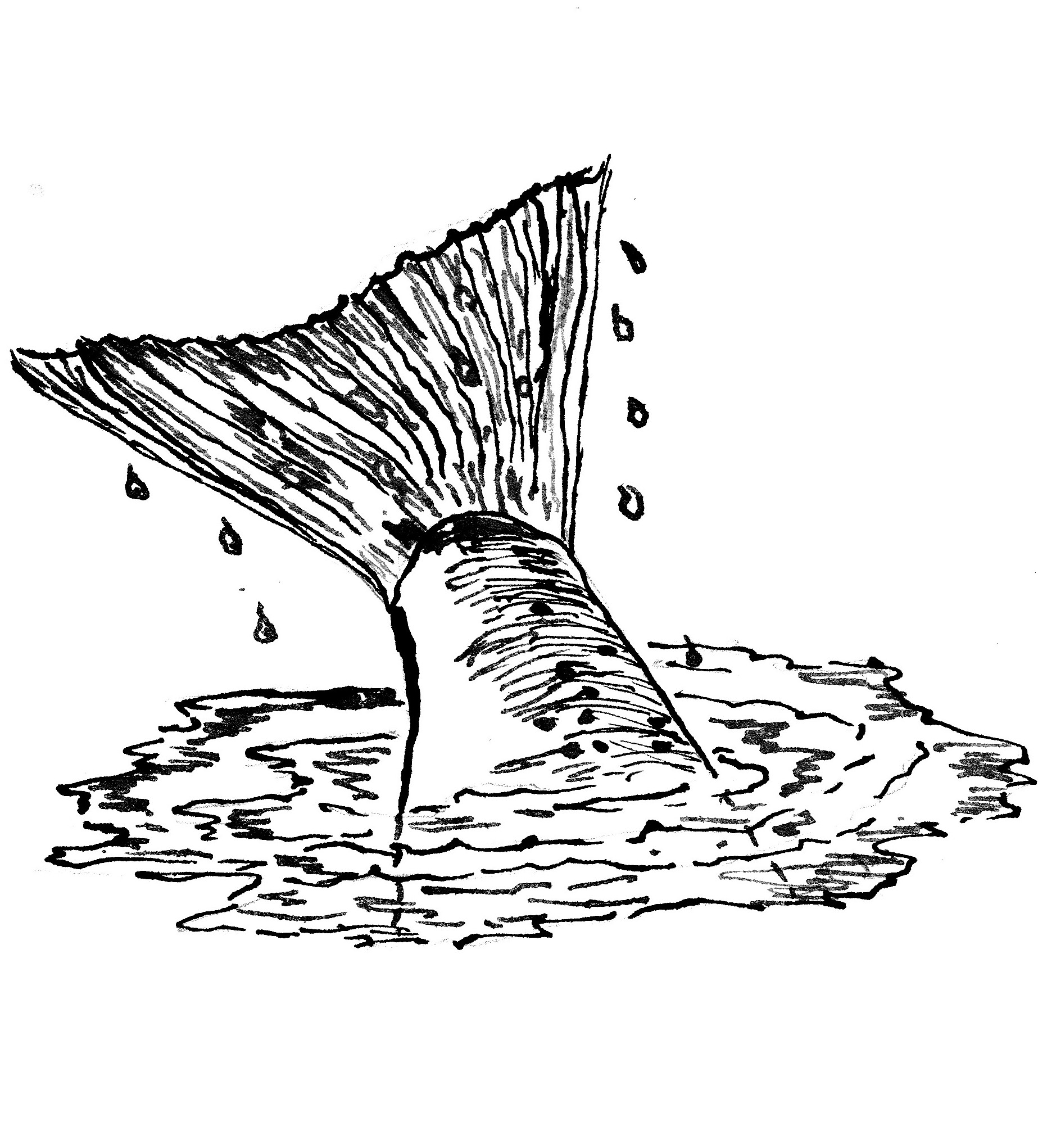

The howling winds of January will die away, the rivers will subside and the sun will shine.

That awful dread of wasted days whilst staring wistfully at scudding clouds and pouring rain will once again be replaced by lightness of heart and hope as once more the sun shines.

The road to the river will be a joyful journey and the trout await, fat with the fruitfulness of nature’s bounty.

That bounty will largely consist of terrestrial insects blown to the water by the gales we have heartily cursed.

The height of summer brings beetles to maturity and their flights set the evenings abuzz as they search for mates.

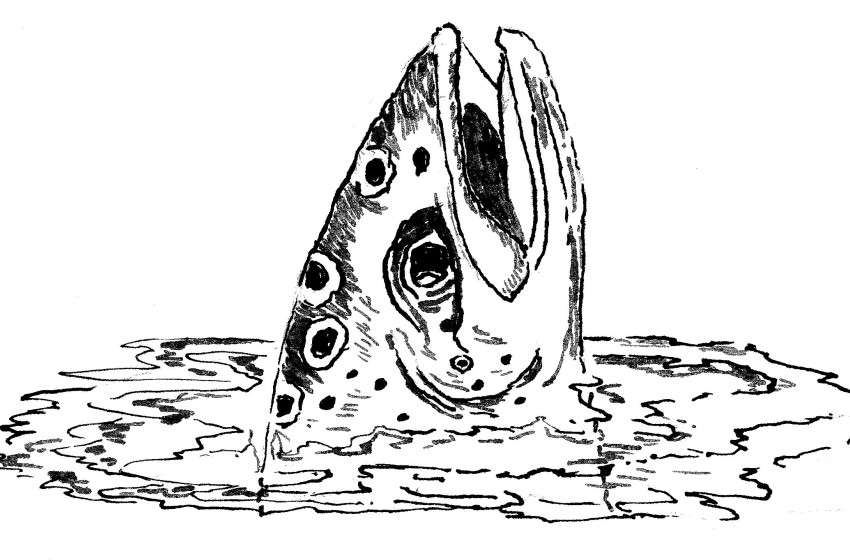

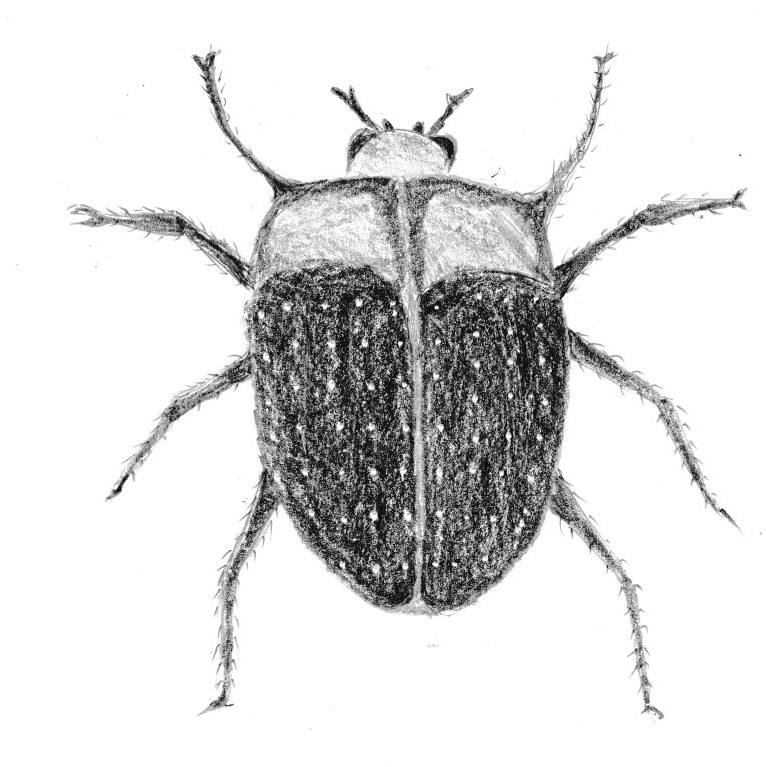

A brown beetle.

Brown beetles hatch from the ground, full of the rootlets of meadow grasses they have destroyed.

But these destructive pests have not finished.

As adults they attack fruit trees both fruit and leaves.

Their only redeeming feature is that they make good trout food, and when the moon is up they fall on the water in vast numbers.

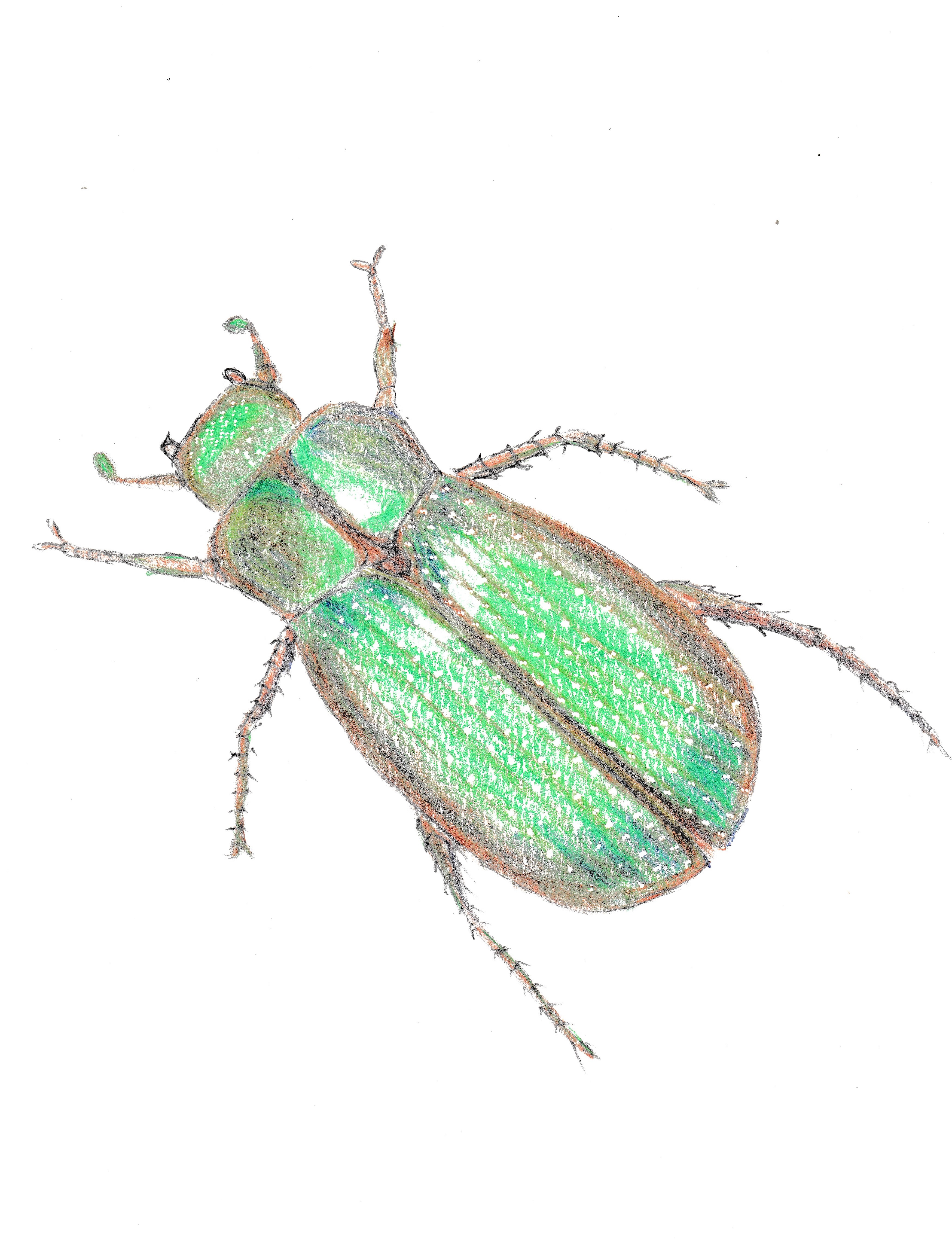

A green beetle.

If you are fishing near a patch of manuka, then the green beetle adds to the feast, followed by scarab beetles and wood borers, all members of the coleoptera family.

The largest of them is the huhu, reaching about 5cm in length, and they bore into dead wood before emerging to fly at night.

Their size makes them quite scary and they are quite capable of giving a good nip if carelessly handled.

All these creatures can be imitated, and night fishing with their imitations can be both rewarding and frustrating.

Brown beetles hatch and fly in such vast numbers that your puny imitation, no matter how well tied, is only one in a floating feast.

On some of the small streams around Wellington I found it easiest to fish in the early morning, just before sunrise.

Visibility is good, the wind has died down and you can fish with a long leader.

Presentation does not have to be perfect.

The plop of a fly on the water can attract fish, even those that have been feeding through most of the night.

I have caught fish so stuffed with beetles that their stomachs have become greatly distended and crushed beetles can be seen through their opened mouths, yet still they rise for more.

Of course, all the principles of dry fly fishing have to followed.

Try and cast to visible fish and drop the fly a few centimetres to the side, so your leader doesn’t cross the fish.

When the fish takes the fly, give it time to get a good grip before striking, and don’t strike too forcefully.

Sometimes adrenalin takes over and the jerky lift of the rod takes the fly out of the fish’s mouth.

Spin fishers using a bubble float and fly can drop a fly into places fly fishers cannot, and where it is legal live baiters using small hooks can cast beetles into fast water.

The hard wing cases of beetles hold well when pierced with a hook.

Willow grubs will be drifting on the breeze.

Watch out for their filaments drifting off the riverside willows.

They are members of the hymenoptera family that includes wasps, ants and bees.

These tiny grubs seem to leave their galls in the heat of the day, when trout have digested their overnight feasts and are ready for another course, so small that they do not seem to be worth the energy of their pursuit.

But trout seem to find them irresistible.

At first, the observer will see fish rising under the willows, and at first glance there are no visible insects.

It takes good eyesight to see the tiny yellow-green grubs on the water.

The are only a few millimetres long and float in the surface tension.

Trout sip them up, rising and falling on the take.

It takes light tackle to present a fly so small in near-still water.

Many years ago I was searching for the right coloured material to tie on a #16 hook to imitate the grubs I saw on the water, and the only coloured material that came near it was from a plastic bread wrapper, that I cut into thin strips.

It worked and for a few years, each summer I would buy a loaf of bread to get the right coloured wrapping.

It was only a small section of the wrapper and I would use it all in one season.

Then they changed the wrapper.

Floss silk was a poor imitation but these days there is a proliferation of materials that will do the job, most of them products of the oil industry.

I use them with a pang of guilt assuaged by their success.

High summer brings out the blowflies, those lovely big bluebottles, denizens of the dung left in the paddocks by cattle and sheep.

Plenty of them fall on the water, specially when chillier evenings make them dozey.

But still, it’s the old mainstays that take the most fish – mayflies and caddis that rise in the evenings and at consistent times during the day.

But still, it’s the old mainstays that take the most fish – mayflies and caddis that rise in the evenings and at consistent times during the day.

When all seems quiet on the river and there are no rises to be seen, a pheasant tail nymph sunk deep in fast water or a weighted hare and copper will pull a fish from the deep when nothing else will cause a stir.

For a hundred years or more they’ve been doing the job and for a hundred more they ever will.