Hugh Creasy column for Feb 2021

- 18/02/2021

- Richie Cosgrove

In the heat of the day, the road surface glistens black with melting tar, and the roadside broom crackles with ripening seed pods bursting and brittle.

Dust rises above them in the still air, and the scent of oily foliage hangs heavy.

The track to the river is dry – even the roadside drainage ditches are parched.

But a short walk in the shade of the willows takes us through a field of Himalayan balsam, seed heads ready to explode at the slightest touch and near desiccation.

Summer storms have given way to sunshine, still days and balmy nights.

cicada

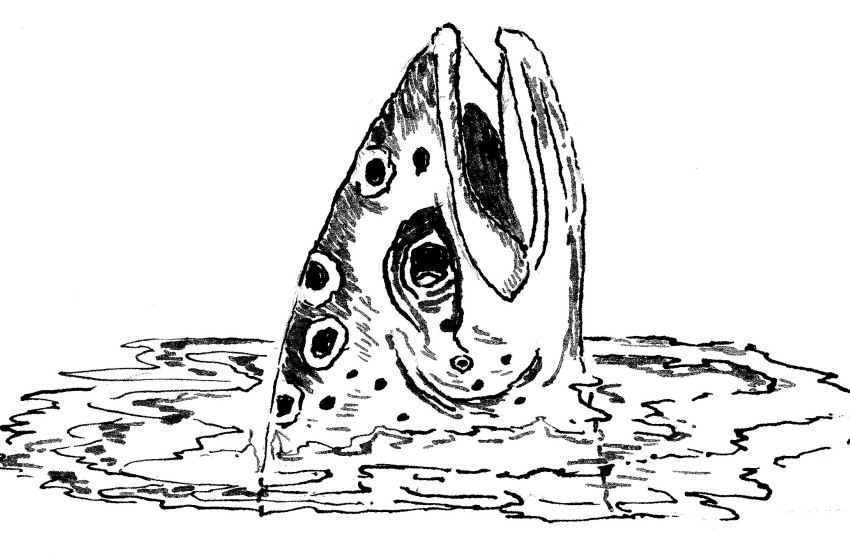

Tree trunks are lined with the shells of hatched cicadas and the adults keep up a rising chorus as the day grows hotter.

In the short grass of a paddock grazed by sheep, grasshoppers leap at every footfall.

A bouldery track leads to the water at the tail of a run.

The only clear water is at the downstream side of large boulders that in spring were the best of holding waters for larger fish.

In mid-summer, the reach is green with algae.

In the shallows fluffy brown growth coats the stones.

It is going to be a slippery trial in wading and casting.

To fish a wet fly would be impossible.

Every cast would gather weed on the retrieve, and nymphing would require pin-point accuracy in casting if you were to avoid the same fate.

A dry fly, though, would, in theory, bob along the surface, minimising risk.

I have found that the Western fly patterns from the United States have far more in common with New Zealand fauna than fly patterns from Europe.

Our rivers are similar in nature being fast flowing from mountainous regions and having fairly short journeys to the sea.

The slow-moving trout streams of the United Kingdom and the fishing methods over still water have only occasional relevance to our topography.

Grasshopper imitations are rarely used here but fished at pool edges where hoppers are disturbed by wind or passing stock they can pull a fish from the deep.

They can be fiddly flies to tie especially if you go to the trouble of knotting herl to imitate legs and trimming deer hair bodies,

the thought of losing such careful creations can be daunting, but have the courage and cast the little precious, it might just pay off.

Then, there’s the Humpy, an all-purpose deer hair fly that imitates most terrestrial creatures when tied in various sizes.

From blowflies to bumblebees, the Humpy can copy them all – it just takes some minor alteration in colour and weight.

Tie on a wing and it’s a cicada. Though it floats, it is quite weighty and makes a hearty splash when it hits the water.

The splash will either frighten a fish or attract one. In the deep south, the nights get chilly in late summer, and cicadas grow dozy as the night wears on.

In the early hours, they drop off the willows and become trout tucker.

By sunrise, trout have become used to their splashes and go on the hunt whenever they hear one.

By mid-morning the natural fall is over and trout are once more suspicious.

Near still water, there may be a hatch of large dragonflies.

They flap around like miniature helicopters, and when the females lay their eggs through the surface tension of the water, they become vulnerable to the snapping jaws of a rising fish.

On a windy day, a Muddler Minnow with a deer hair hackle fished with the rod held high will dot the surface from wavelet to wavelet -- a pretty good imitation of the real thing.

This is where a lightweight rod comes in handy.

A stiff tailwind will keep the line in the air, and by lowering and raising the rod tip you can copy the action of a dipping dragonfly quite successfully.

It’s great fun when a shadow from the deep rises and snatches a fly, sometimes when it’s well out of the water.

These are all the possibilities when I reach the river.

But it’s weedy appearance is not in any way encouraging.

It seems lifeless. No insects are rising and no breeze ruffles the surface.

There is a line of current through the water free of weed.

It’s only a metre or so wide at its widest point and runs for 50 metres or so before it reaches the tail of the pool.

To cast a fly along its length would require wading across slime-encrusted stones.

There is a gravelly track to a good casting position near the tail of the pool.

There is a gravelly track to a good casting position near the tail of the pool.

Gravel is much easier to negotiate than slimy boulders and stones.

But if I caught a fish there would be a hard exit to the shore.

Oh, well, the sun is going down and the fish must come out to feed at some stage, so I will tie on a brown beetle and wait for twilight.

It’s going to be awkward work, but if I have planned things right it just might be successful.