Hugh Creasy Column for December 2020

- 19/11/2020

- Richie Cosgrove

There is a chill in the morning air, and the moon hangs above the horizon, soon to disappear as the sun rises.

We came from low valleys, through beech forest with moss-strewn branches, and low-branched fuschia, still holding sugary berries – delicious treats for the weary.

For company we were joined by fantails and robins and warblers, each in succession as we gained altitude.

The sound of the river grew faint and its vast flow was reduced to gentle streams through tundra-like clumps of tussock.

In the lowlands the dominant odours were of manure and lemon balm growing in clumps on the riverbank.

The heavy scent of Herb Robert rose from the pathway with every scuff of booted feet.

As the day warmed grasshoppers leapt to cover, easy pickings for starlings and blackbirds.

At altitude we hopped over clumps of bidi bid then dodged sharp-tipped spaniard.

Musk-scented celmisias dotted the scree faces and in the shade of a massive boulder a vegetable sheep spread its close-grouped leaves.

We were in kea country, and they soared between ridges, calling and answering, their shrieking tones ringing and echoing through the peaks.

The climb came to an end and the descent began, thigh burning and more painful than the climb.

But in the valley bottom a glimmer of water drew us through coprosma and mountain totara to a streamside where tussock shadowed the water.

Riffles and runs flowed in gentle succession, knee-deep in the pools and over clean gravels that gave good grip.

It was a kindly valley, easy going after a hard climb and we would follow the flow to less kindly country.

It took a few minutes to assemble rods and lines, to tie on flies and wipe sweat off polaroids, then on opposing riverbanks we set off to spot fish.

It would have been a lot easier if we had been travelling upstream instead of down.

We had to stay well back from the stream’s edge and try to spot fish from high points.

But there was no shortage of fish to spot.

They took up station at the base of every riffle, usually a single fish with another further back in the pool if the pool was large enough.

As the sun rose higher the fish stayed close to the banks and appeared as dark shadows, every now and then breaking surface to take an insect.

These fish had rarely been hunted, and readily took a fly of almost any pattern, though the splash of too heavily a weighted nymph would send a shiver of nervousness through them.

We crimped the barbs of the hooks we used and returned all fish to the water.

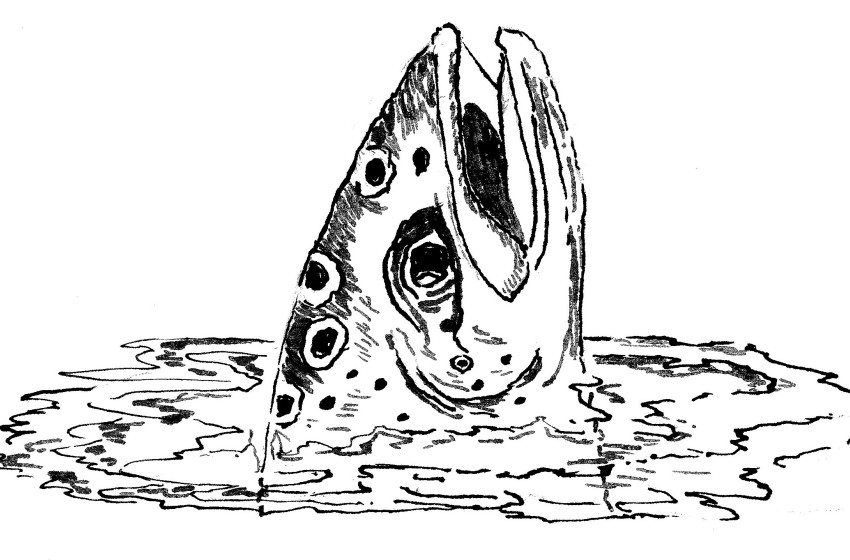

They were fine-conditioned brown trout about a kilo to a kilo and a half in size.

The descent brought us to an outlying clump of matagouri, and we knew the going would get a lot harder.

It was time to camp for the night, though it was only late afternoon.

Every matagouri bush seemed to have a resident family of rabbits living in its roots.

Their diggings dotted the landscape, and Ted took a rifle to higher ground.

The sound of his shots came as dull thuds and we knew we were in for a tasty stew before bedtime.

Hunger made even the dehydrated potato taste good and the stew was superlative.

Sleep was dreamless. Exhaustion leads to restful nights, and we woke invigorated.

At lower altitudes the fish became larger and sparser, and it was no longer possible to cover both sides of the river without making some dangerous crossings, so we relied on spotting fish from higher ground or from atop large boulders that littered the landscape.

After a descent of a few hours we moved into beech forest once more, and disturbed some moulting Canada geese accompanied by juveniles whose antics in trying to get aloft and away from us grew quite comical.

Geese and paradise ducks with the occasional blackback gull seemed to be the resident large birds and as we descended further they were joined by pied stilts and terns.

The valley we travelled widened into flats and the fish became harder to find, but the weekend was almost over and we were sated with the quality of the fishing and the beauty of the landscape.

The valley we travelled widened into flats and the fish became harder to find, but the weekend was almost over and we were sated with the quality of the fishing and the beauty of the landscape.

People were moving about, driving tractors and mending fences and the odours of forest and wetland were replaced with the smell of ordure and diesel smoke.

We reached the car park in the early afternoon, took off our packs, packed away lines and rods and fishing vests and drove to town where Ted said: “I feel like a pie,” so we stopped at the pie shop and breathed in the scent of steak and cheese and baking pastry and mince and onions and all those wonderful odours of civilisation.

But in the evenings following we remembered the smell of the forest, the odour of moss and the sound of clean rushing water and a billy boiling to make tea, the kea’s call and the deer sign in the soft mud at the river’s edge.