Hugh Creasy Column

- 24/09/2019

- Richie Cosgrove

“It’s simple, really,” said Sage, “Go deep, go heavy, go big.”

We watched the river’s flow – its backcurrents and rapids, small and large, it’s volume, about twice its average in summer.

The water was discoloured with snowmelt, making any attempt to cast to visible fish impossible.

A few kilometres away, at the mouth, whitebaiters were having fun, some with long-handled dip nets that scooped fishy treasures from still water at the edge of the river’s flow.

It was cold. There was enough snow, still on the tops, to chill the breeze that flowed off the Alps.

Sage assembled a rig that he had built himself.

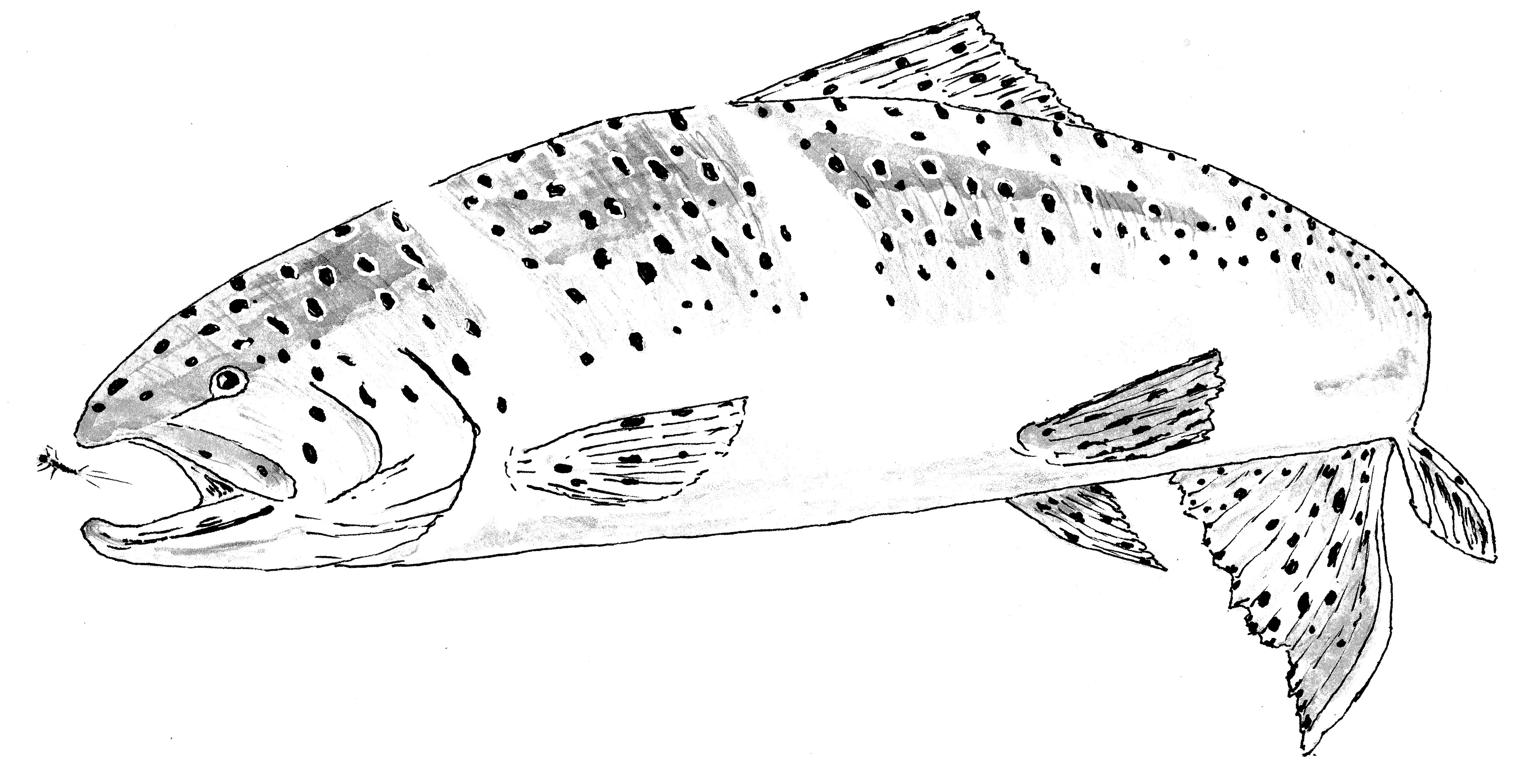

An 8-weight rod, an old floating line with about five metres cut off the tip and replaced with five metres of 8-weight fast sinking line with a three metre leader with a tippet strength of three kilogram.

It was his own invention, and he had been using it on these waters for about 20 years.

Sage caught a lot of fish, but I wondered if this was because he spent many hours on the water, rather than his unconventional approach.

The assembled rig was beautifully prepared, with all knots sealed and the flylines neatly spliced.

He cast and the line went smoothly through the rings and dropped the fly at head of a rapid about 20 metres upstream.

The drift was perfect and the retrieve rapid before the sinking section of line came through the rings and was ready to cast again.

Sage always spoke in a rumbling baritone, each word perfectly enunciated and expelled with such sincerity that his rather crafty sense of humour remained largely hidden.

We called him Sage because he sounded sagacious.

It had nothing to do with the brand of his equipment.

I wandered upriver about a kilometre and cast to a deep pool at the foot of a rapid.

It looked like good holding water.

The clunky, overweighted nymph sank like a stone and tumbled through the pool and into a reach where it was retrieved.

It felt all wrong.

There was no balance to the rig.

Big flies have their limits and this rolling monstrosity had no appeal to either man or fish.

A lighter stonefly imitation felt much better.

Its drift was smooth, with an occasional touch on the bottom to prove it was at the right depth.

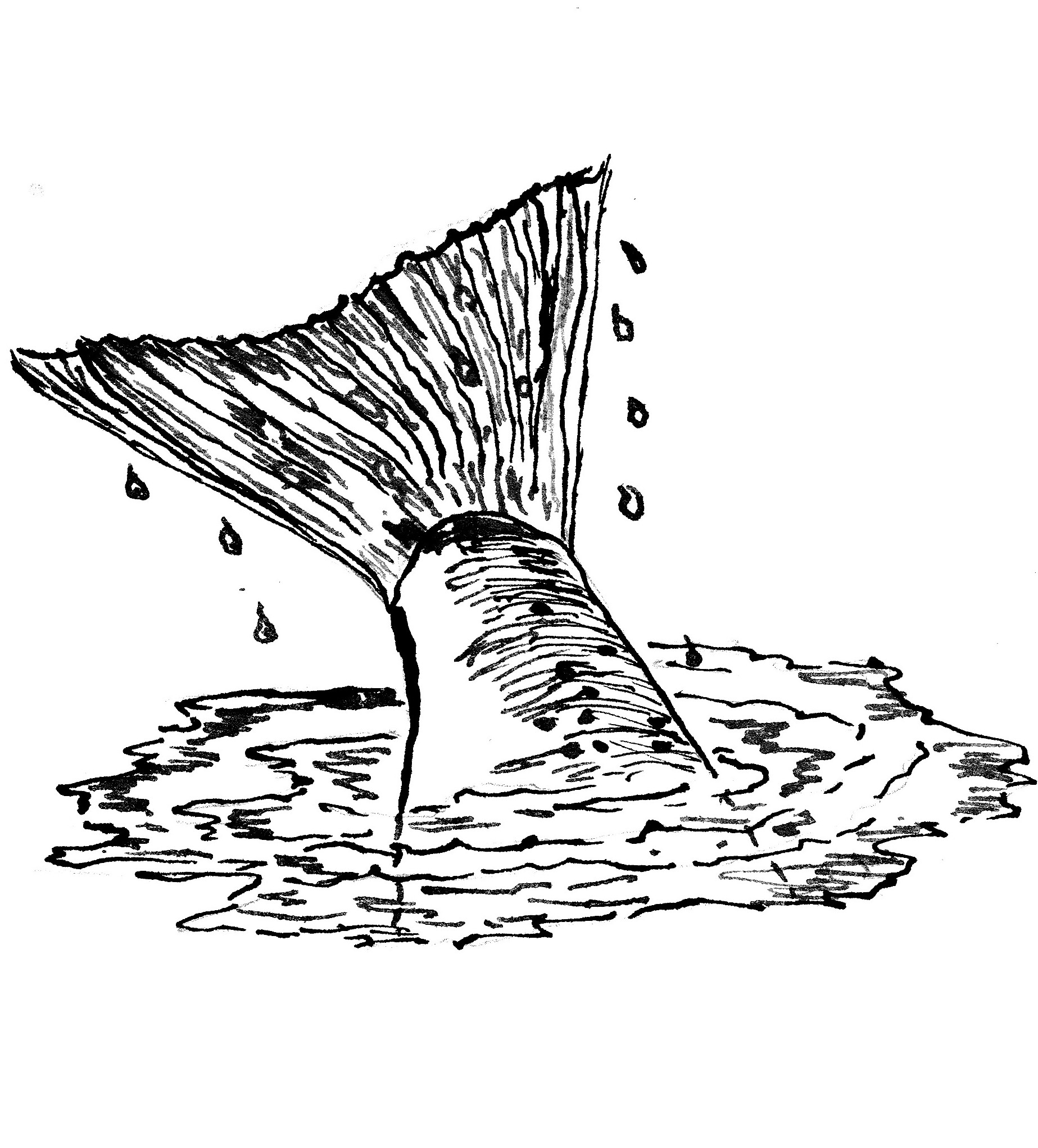

A half dozen casts were needed before a good fish took the fly.

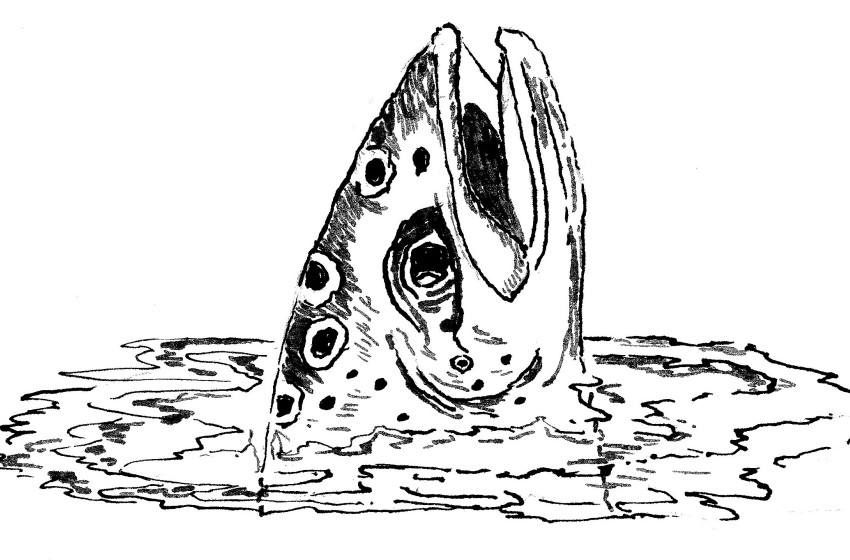

It was a kilo fish, light in colour with none of the bronze glow that marked fish in the nearby lakes and their feeder streams.

It was a kilo fish, light in colour with none of the bronze glow that marked fish in the nearby lakes and their feeder streams.

With the whitebait running and visible in shallow water alongside the main flow, I thought a galaxid imitation might pull a strike or two.

It did and a couple of hours of casting were well rewarded.

The cold, though, was intense and I returned to Sage who was boiling water on a Coleman spirit burner. The billie tea was welcome and warming.

The snowmelt discolouration kept us out of the water. Wading was dangerous and all casts were made from the bank.

Earlier in the week Sage had been hunting the tops, above the forest cover of mountain beech and broadleaf.

He had a slip and landed in a clump of spaniard that pierced his leggings and drew blood.

The uncertainty of footing and lack of game dented his confidence, and the weight of rifle and pack dampened his enthusiasm.

Animals may be scarce on the tops but there is no shortage of sign lower down.

Fishing the lower reaches was much more inviting, so he joined me on the river, where the worst plant pest was fields of bidibid.

When the wind died in the evenings, we could hear the tumbling roar of ice and snow in the high alps and the crackle of melting ice on the scree faces.

When the wind died in the evenings, we could hear the tumbling roar of ice and snow in the high alps and the crackle of melting ice on the scree faces.

At night, flights of Canada geese passed over and their plaintive calls echoed from the valley sides.

I am of an age when hunting the tops was a distant memory, and even wading in wild water was something I seek to avoid, but there was always the pleasure of being in wild places that drew me.

The occasional fish caught was a bonus.

In late winter and early spring, in sheltered valleys there can be an almost tropical atmosphere on the West Coast, and the great hatches of mosquitoes and sandflies are testament to the warmth of the season even if the nights are freezing.

Deer appear on the faces in the evenings, and their hoofprints are scattered on every patch of damp sand we cross.

Sage is tempted to have an evening hunt, and as the sun is setting I retreat to the warmth of our camp and a fry-up of sausages and eggs livened up with tomato sauce and mustard.

It does nothing for my arteries but is a pleasant weight on the stomach when night falls.

The forecast is good and fish are in the pools.

In the morning I will find out if we will be eating venison steaks for the rest of our stay.

There is bird call that sounds like a weka which would be unusual this far south, and it is something to ponder before sleep overtakes me.

Hugh Creasy